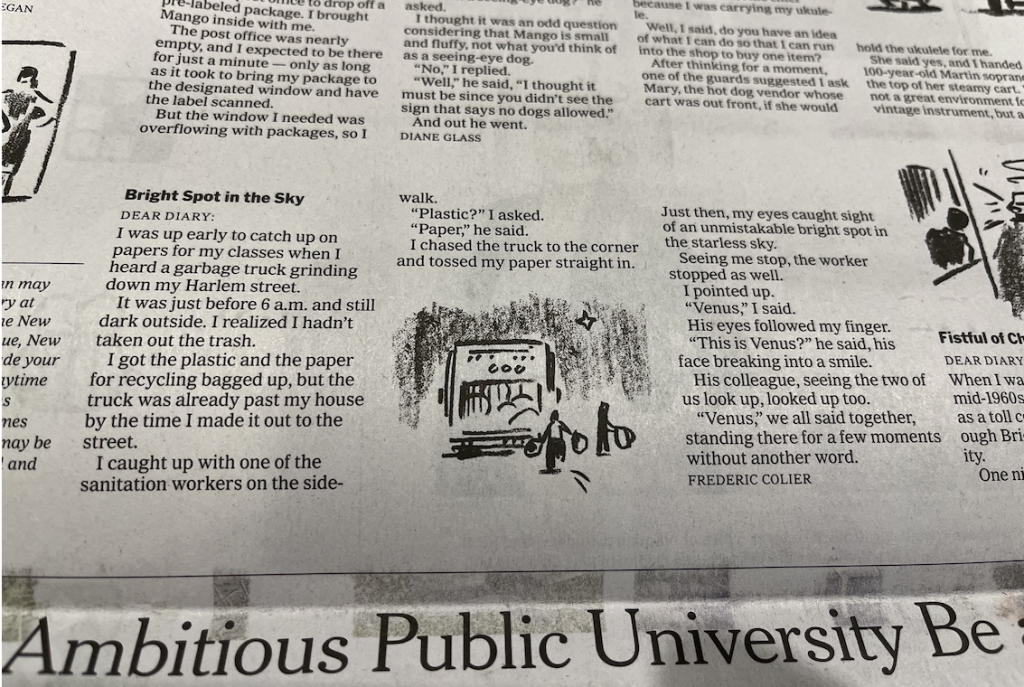

The New York Times (NYT) published another of my stories, “Lifeline.” See Sunday edition 08/24-25/2024. It goes without saying that this story, once again, was so mighty important that it needed to be shared…

The New York Times (NYT) published another of my stories, “Lifeline.” See Sunday edition 08/24-25/2024. It goes without saying that this story, once again, was so mighty important that it needed to be shared…

Desert Weeds is a psychological thriller, written and directed by me. It is a short plot-driven film (a student film), which was designed to showcase ‘talent.’ Looking back at it, the story does feel ‘operatic.’ It was shot on Mini DV (that feels like a different lifetime) over two days in Weston, CT, in the early Spring 2004.

After losing her son during the Iraq War, a still-grieving Louise (Patricia Geri Russell) is forced to give up the control of her company. She has been too distracted for her backers… Craig and Susan (Sayra Player) have gone broke, spending their savings in unsuccessful IVF treatments to have a child. Craig (Michael Williams), in desperation, comes up with a scheme to raise money. His first testing ground, Louise . . .

I am taking a break from my current writing marathon to reach out to all the literary agents out there. Last three years, up at 4 am every day, 7 days a week, with no break, to complete my project on René Guénon (1886-1951), Beyond the Veil of Modernity. I am indulging because I am within distance from the finish line, 30 pages, maybe 40 top. Shooting for the end of July… Ok, maybe mid August. In any case, it is round the corner. It is a non-fiction project, dealing with Traditionalism, and spiritual authority and temporal power… 150 K words, researched and all…

I imagine many of you are thinking, René who? I would not blame you since virtually no one knows who he is… and yet all the far-right politics of late link him to their ideologies. It is true in Europe, Brazil, Russian, and the US. Strange if not paradoxical move, given that Guénon was a spiritual being, a Frenchman who converted to Islam. Or maybe not, his spirituality veiled his politics? . . . That the premise of the book.

It is a unique project, since no comprehensive book in the US (or in English for that matter) has ever been written exclusively with René Guénon (and his world) as the central character. Only chapters here and there . . . often very misunderstood if not mis-portrayed.

I was in Catalonia (Cataluña) last month for a very special reunion . . . commemorating the 30 years of Sin Prevision, a rock band I played with when I lived in Barcelona. . . The first half of my life was all about music. This is all I did from the moment I woke up. I practiced and practiced more, years in and out … guitar, bass guitar, drums, and songwriting, you name it. . . I saw hundreds of bands, and played everywhere I could… This was then.

Over the last two years, I have been composing new material. I played a short acoustic set, showcasing new original songs, before jamming with Sin Prevision on bass, resulting in a major case of mean, but well-deserved, blisters … This was my first concert in more than 25 years… and I anticipate releasing an album before the end of the year, under Troublebadour, the name I used then. Here is the picture of Sin Prevision and its multiple incarnations throughout the years.

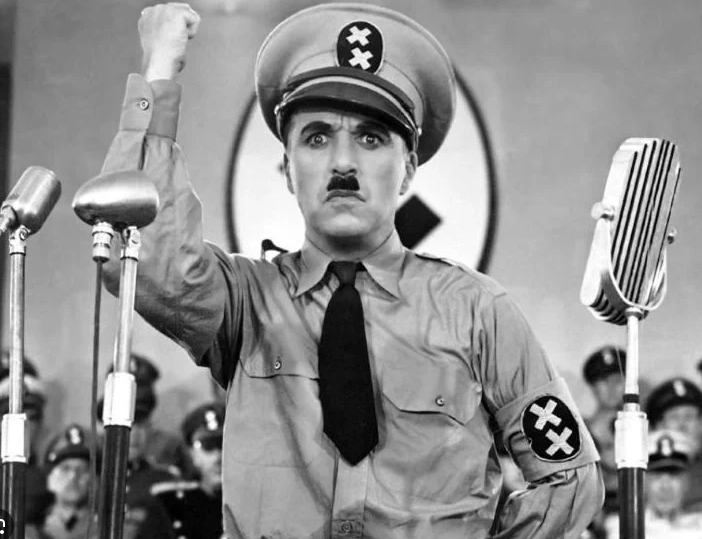

“A Fable for the New Millennial: What Dictators Taught Me About Writing Fables”

by Frederic Colier

Writing fables demands universal wisdom. Nowhere else is this truer than in politics. I speak from experience. For years, I utterly failed at writing political fables. Success only came from outside of it. My failure was tied to my ignorance of the importance of truth. Call it a failure of imagination or lack of talent.

My efforts were not in vain, however. First, I came to learn that dictators are terrified of fables. Nothing frightens a dictator like a well-honed fable for children. Myths are much better equipped for politics, and dictators are the most comfortable when evolving in myths. With little concerns for truth, myths’ only prerequisite is a fertile imagination. A fable will fail if it tries to dress with the garments of a myth. The myth will look ridiculous with those of a fable. Myths demand high drama and exaltation. Dictators thrive on the heightened imagination of myths.

Second, I learned that dictators abhor fables. To write a successful one, a fable must produce a sobering lesson that can stand the test of time and takes responsibility for its consequence. Everyone knows the core message of “The Turtle and the Hare,” “The Grasshopper and the Ant,” or “The Boy Who Cried Wolf.” Whoever reads them can infer the meaning. This is true in Europe, Africa, or Asia. We called these lessons morals. Morals may have originated from socio-religious concerns, but they parlay an ethical code for social conduct. Most fables have managed to remain as relevant today, through all types of circumstances, as they were 3000 years ago.

This moral endurance is useless for dictators. The only permanent truth is the myth about the dictator. Only personality matters in myth, the more exalted the better. In fables, where morals reign supreme, characters, no matter how they behave, have little relevance. They only represent the failure of their moral conduct, and they can be substituted for other characters. Replacing the Hare, the Turtle, or the Boy with another Hare, Turtle, or Boy would not change the nature or outcome of the story. The fable of an everyday man seeking to become a king would suggest that the story will not end well, or in humiliation as in “The Emperor’s New Clothes.” Preachy endings make a poor bedfellow with the celebratory stipulations of someone seeking a mythic status. It would be a mistake, for example, to claim that the myth of a man who wants to rebuild a crumbling empire is about a moral lesson.

Given the constant demands of the dictator, myths are never about long-lasting truths. They are only concerned with any bright outcome. And the subject can never be replaced by any other subject. In fact, myths only celebrate the greatness of its subject. The myth of an everyday man, who claims to have a special destiny to rule over a vast number of people, without their consent, expects the same people to suspend common sense and believe in his supernatural power. This is what I failed to comprehend.

This failure made me realize that as much as fables have steady narratives, myths do not. The characters of fable live forever, whereas the subjects of myth are prone to mortality. The dictators must constantly update their wardrobe not to run the risk of falling out of fashion. Maintaining a myth current requires an unfettered, scruples-free, imagination. The would-be dictator must prove his extraordinary talent over and over to prevent the masses from questioning his actions. This unending process forces myths to escalate their display of fortune until the people, on the ground, feel dazzled by the burning rays of their fanatical mission.

Satisfaction is a big component of a fable’s resolution. Given their precarious nature, a myth never yields clear satisfying results. The endless quest of a shifting narrative explains why it is hard to learn anything from a myth. What can be inferred from a mosaic of disparate ideas cobbled together? In a fable, a character would see through the problem at once and expose the subject’s flaw. It is not advisable in a myth, at the risk of exposing its motive.

Preserving the integrity of a myth is therefore paramount. Dissent must be readily suppressed. The myth-monger must target the myth-busters: other politicians, journalists, and scholars, down to the single mother who commits high treason for requesting a foreign song on the radio to celebrate her daughter’s birthday. Nothing must threaten the image of the dictator. The survival of a myth is directly related to the darkness of its defensiveness. No myth no dictator. A fable’s moral is set in stone. No one can alter it. Given my lack of critical understanding about the nature of fables, no doubt I was setting myself for failure.

Yet, I made an unsuspected discovery. A myth’s ravenous instinct of preservation, sooner or later, triggers its own comeuppance. The more extreme the myth, the fiercer the reaction. Human history abounds with cases. The allies decimated the Aryan Nazi myth. Mussolini’s or Ceausescu’s myth did not fare much better. This reversal takes place when the dictator, by attacking its coveted audience, makes the myth prone to unpredictability. This explains why, at some point, the dictator will experience a mighty fall. It may be triggered by a boy shouting in the street about a bad outfit. The downfall of three mythic dictators, in Tunisian, Libya, and Egypt, started with a street fruit vendor in Tunisia. The lesson is not that the day a myth starts forcing its clothes on everyone to justify its existence, though it is true, it de facto incubates an unpredictable street-vendor. The valuable lesson is that myths never proceed with caution. They are so blind to their greatness that they fail to see that inside each one of them hides a fable, pregnant with a hard-earned moral, eager to speak its truth. So, the boy in me is now shouting that a myth without a coat reveals nothing but a powerful naked fable. A terrifying revelation for a dictator. We knew this all along.

“Of Wanderlust” was my very first short film (a student project). This psychological thriller was shot in the Fall of 2003 on Mini DV (SD). 20 plus years ago. Back then HD was just coming out and was truly out of reach, for small productions . . . Shot over two days in Weston, CT, the film features Armand Anthony in the lead role, Griz; Noelle Holly as the traumatized Regan, Mike Williams plays the frustrated lover, and the now-defunct Karibi Fubara, Jake, the witness. I spent five months laboring on the film: writing, producing, directing, and editing both footage and sound. The film had a nice festival run during 2004-05. It got me to visit the States, and it even collected awards on the way . . . More than once, audiences asked me why not turn this story into a feature . . . The story does not really abide to the short-film formula. It has a commercial tone and the structure of a compressed feature. They had a point. The truth, however is that I’m not sure this story has the spine to carry a 90 mn arc and remain both interesting and suspenseful. Maybe someone out there… ? This short film was designed to be a business card . . .

There was a popular series of illustrated books when I was in England in the late 80s’. It was an unusual series. A silly-looking guy, with thick glasses, and red ski hat, walking around with a walking stick, a backpack, and a white and red stripped shirt, through complex imaginary landscapes. That was the world of Wally, as in “Where is Wally?” Everyone read those books, spending hours to locate for “the silly guy” buried in the various scenery.

When the series was transferred to an American audience, the name was changed to Waldo, which is a weird adjustment, since the new name conveyed nothing of the original title. A Wally is a Wally, not quite an idiot but a stupid or silly person. Waldo carries no meaning whatsoever. Basically the English cheekiness was lost in translation.

Attached is a photograph from a PEN America event back in January 2024. Can you find the Wally/Waldo in the picture? Clue: This Wally attended the event, and his face landed on the main photograph of it. He is standing, clearly a victim of imposter syndrome, along the crop of the best young emerging writing talent in NY. Next to him, Ayana Mathis.

In case you’ve missed it, last Sunday (12/31/2023) the New York Times published a very important piece of mine . . . What a beautiful way to wrap up the year. Planets must have been on my side . . .

(Dec 08, 2023) You may not be aware . . . But I interviewed Karl Ove Knausgaard back in 2012, before he achieved a worldwide fame with his six-volume autobiographical series My Struggle as part of my own TV series, Books du Jour. The interview has just been published by the University Press of Mississippi, along many other in-depth conversations from the literary landscape. Bob Blaisdell did a remarkable job editing all these conversations in this must-have book. Whether you are a Knausgaard fan or simply a curious aspiring author or reader here is your chance to get a close look at Knausgaard’s creative process.

If you do not know who Douglas Rushkoff is, it is not too late to catch up. You will not regret it. He is the Naomi Klein male version. While I am not sure, he would appreciate I say this, this is, if I am right, his fifteenth plus books on culture, the digital economy and media, and he only gets better, clearer, punchier and to the point, with each new book. Rushkoff knows how to inspire and shock the crowds by revealing flaws and exposing false assumptions. His unique vision of the Techno-hyper-mediatized landscape is a perception we cannot do without. In this new book, “Team Human,” Rushkoff zeroes in on the pervasive effect of our most cherished human accomplishment: our technology, and what it is doing to you, to us, to our society . . . Here I will defer my authority to his clarity of thoughts and future projections. Get his book now.

If you do not know who Douglas Rushkoff is, it is not too late to catch up. You will not regret it. He is the Naomi Klein male version. While I am not sure, he would appreciate I say this, this is, if I am right, his fifteenth plus books on culture, the digital economy and media, and he only gets better, clearer, punchier and to the point, with each new book. Rushkoff knows how to inspire and shock the crowds by revealing flaws and exposing false assumptions. His unique vision of the Techno-hyper-mediatized landscape is a perception we cannot do without. In this new book, “Team Human,” Rushkoff zeroes in on the pervasive effect of our most cherished human accomplishment: our technology, and what it is doing to you, to us, to our society . . . Here I will defer my authority to his clarity of thoughts and future projections. Get his book now.